St. Teresa of Avila is recognized as mystic and writer living in an age of political, social and religious upheaval. Teresa’s life work deeply inspired reform in the Catholic Church.

Born Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada in the Castilian city of Avila in 1515, Teresa’s paternal grandfather, Juan Sánchez, was a wealthy converso merchant who was prosecuted by the Toledo Inquisition in 1485 for being a judaizante, a secret practitioner of Jewish customs. After a time of public shaming which included Teresa’s father Alonso, the family moved away to Avila to make a new home.

In her young life, Teresa experienced the death of her mother, profound grief, a brief convent education and personal illness.

Teresa entered the Carmelite monastery of the Incarnation in Avila on 2nd November 1535 against her father’s wishes where she spent many years. She found the convent to be an easy-going community of upper-class women who did not observe the rules of cloister. For much of her life, Teresa had been devoted to prayer. By the age of 40, she was dramatically called back to the practice of completive prayer.

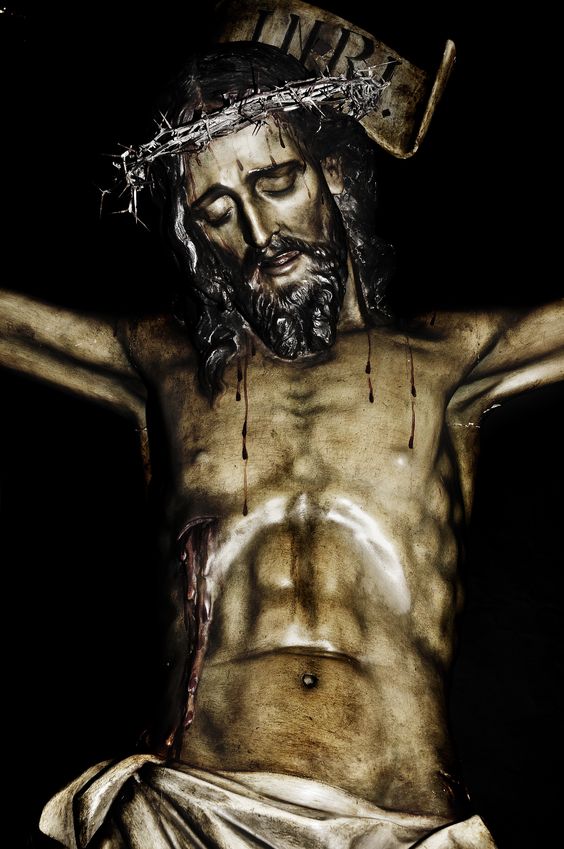

An image of the suffering Christ brought Teresa to a personal awareness of how much our salvation cost Jesus. Encouraged by the example of the penitent Magdalene, she placed all her trust in God. It is trust that set her free from having to work for her own salvation and allow God to work in her. Teresa continuously reflected and sought to understand and integrate her experience of life and prayer.

As a woman, Teresa stood on her own two feet, even in the man’s world of her time. She was “her own woman,” entering the Carmelites despite strong opposition from her father. She is a person wrapped not so much in silence as in mystery. Beautiful, talented, outgoing, adaptable, affectionate, courageous, enthusiastic, she was totally human. Like Jesus, she was a mystery of paradoxes: wise, yet practical; intelligent, yet much in tune with her experience; a mystic, yet an energetic reformer.

Teresa was a woman “for God,” a woman of prayer, discipline and compassion. Her heart belonged to God. Her own conversion was no overnight affair; it was an arduous lifelong struggle, involving ongoing purification and suffering. She was misunderstood, misjudged, opposed in her efforts at reform. Yet she struggled on, courageous and faithful; she struggled with her own mediocrity, her illness, her opposition. And in the midst of all this she clung to God in life and in prayer. Her writings on prayer and contemplation are drawn from her experience: powerful, practical and graceful.

A woman of prayer; a woman for God, Teresa was a woman “for others.” Though a contemplative, she spent much of her time and energy seeking to reform herself and the Carmelites, to lead them back to the full observance of the primitive Rule. She founded over a half-dozen new monasteries. She traveled, wrote, fought—always to renew, to reform. In her self, in her prayer, in her life, in her efforts to reform, in all the people she touched, she was a woman for others, a woman who inspired and gave life.

In 1970 the Church gave her the title she had long held in the popular mind: Doctor of the Church. She and St. Catherine of Siena were the first women so honored.

The feast day of St. Teresa of Avila is October 15.

Recommended Readings

As we celebrate the 450th year of St. Teresa’s birth, take time to experience and explore her life and writing:

- Interior Castle

- Meditation on Song of Songs

- The Way of Perfection

- Let Nothing Disturb You

- A Life of St. Teresa of Ávila by Herself

Contributors:

Fr. Frank Latzko, Erica Saccucci , Dean Vaeth, Fr. Greg Burke, OCD

Let nothing disturb thee, nothing affright thee; all things are passing; God never changeth.

– St. Teresa of Avila

Image Credits

- Jesus Suffering: Copyright: 123RF Stock Photo

- St Teresa stained glass: By w:es:Usuario:Xauxa (http://es.wikipedia.org/) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons