I moved into St. Teresa Parish in September of 1969 as a college student on a semester “abroad” on urban studies in Chicago in a program sponsored by the Associated Colleges of the Midwest. My apartment was at 2036 North Halsted Street over the Guild Bookstore, next door to Benny’s Pizza and just down the street from the People’s Law Office. The smell of pizza mingled with the smell of leaking gas in the apartment and the sound of rats in the walls.

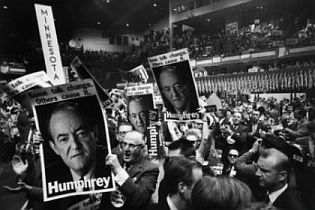

The city was in the midst of fallout of the National Democratic Convention held in Chicago in August 1968. Vietnam was still on; protests continued; the Chicago Seven went on trial starting on September 24, 1969; Studs Terkel writing and speaking; Saul Alinsky was organizing; the Black Panthers Party Chicago, chaired by Fred Hampton, was running medical, social, breakfast and political programs on the west side.

The city was in the midst of fallout of the National Democratic Convention held in Chicago in August 1968. Vietnam was still on; protests continued; the Chicago Seven went on trial starting on September 24, 1969; Studs Terkel writing and speaking; Saul Alinsky was organizing; the Black Panthers Party Chicago, chaired by Fred Hampton, was running medical, social, breakfast and political programs on the west side.

Shortly, after I moved in, the Young Lords Organization took over (with the full complicity of the Methodist church) the United Methodist Church on northwest corner of Dayton and Armitage that became The People’s Church and is now a Walgreens. The Panthers and the Lords were mostly composed of young men in their 20’s and early 30’s and many had served in Vietnam. Their goals were to establish free breakfast, medical care and other social programs and to become a viable part of the political process. Contrary to rumor, none of the Chicago members of either of these organizations was violent, but most of the key Chicago Panthers (except Mark Clark who escaped out a skylight) were assassinated by the Chicago Police on December 4, 1969.

The territory of St Teresa Parish was divided between two younger gangs who hung out on street corners, mostly on Armitage. These younger men were not interested in social or political programs, just in territory and testosterone. The Corp members were white and held sway east of Halsted; the Latin Kings were Hispanic, mostly Puerto Rican, and reigned west of Halsted. Prior to the murder of Hampton and his fellow Panthers, there were no gun incidents involving these younger gang members.

The territory of St Teresa Parish was divided between two younger gangs who hung out on street corners, mostly on Armitage. These younger men were not interested in social or political programs, just in territory and testosterone. The Corp members were white and held sway east of Halsted; the Latin Kings were Hispanic, mostly Puerto Rican, and reigned west of Halsted. Prior to the murder of Hampton and his fellow Panthers, there were no gun incidents involving these younger gang members.

There was a fair amount of conspicuous drug dealing, however, mostly heroin. Pivotal locations were the building on the alley on Sheffield immediately south of the 7-11 Store and, under the Armitage el tracks at the Brown Line station, mostly north side.

Legitimate neighborhood commerce was made up of anchors like Armitage Hardware and Shinnick’s Drugstore and lots of small bodegas and restaurants.

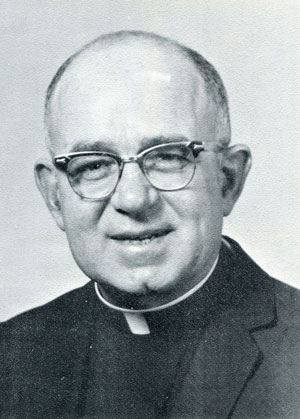

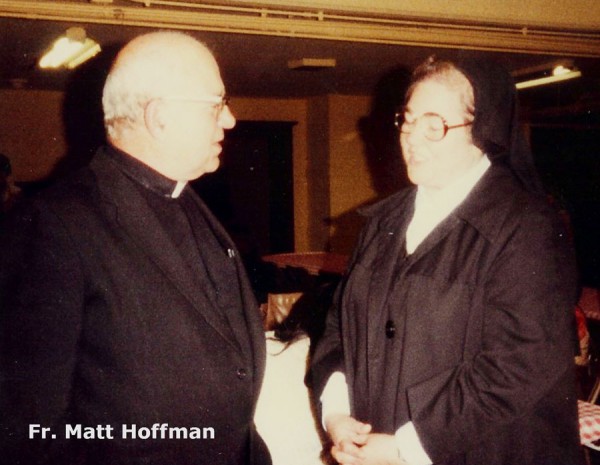

In the midst of this stood St. Teresa, an oasis of peace and tolerance under Father Matthias (born Howard) Hoffman assisted ably by Sister Hildegarde and her order in the school. St Teresa was poor and diverse and there were a lot of challenges. The congregation was split between those of German background and those of Hispanic background, with a few others thrown in. Matt Hoffman would describe the squabbles between his German parishioners and Hispanic parishioners over proper food for a celebration, the date for the Breakfast with Santa party, imagined slights based on cultural misunderstandings, sigh and say: “If people would just speak with a little more understanding or listen to each other a little more carefully, these things would never start.” Shaking his head kindly and uncomprehendingly as to the genesis of a particular spat, he would pour his personal oil on troubled waters and wounds, often successfully. He spoke German, English and Polish from his youth and arranged several long stays in Mexico to learn Spanish, which he also spoke fluently. Every single parishioner believed that he understood her or him fundamentally.

Father Matthias Hoffman, Pastor 1968 – 1980

Many came to the rectory seeking help of all kinds: prayers, a hospital visit, anointing for a dying friend or relative, advice, money, bus fare and food. He never turned anyone away, parishioner or not. He always answered the phone or the door personally if no receptionist was working.

The sisters with Sister Hildegarde had their own challenges including a very mixed school population and many families in the school struggling to make ends meet. In addition, they dealt with drug dealing in their gangway, often recovering and disposing of balloons of heroin and, on two occasions, finding dead bodies in the convent gangway. That required a call to the police, but otherwise they seemed unfazed.

The rectory and church were both in need of repair and what we could afford to repair was repaired. Sometimes the solution was buckets for leaky roofs or just making do. Since our homes had the same issues, this was not anything unusual.

But the Spirit, that was the key… in spite of the drugs and the gangs and the cultural differences and the fact that none of us had much in the way of this world’s goods. The Spirit was one of acceptance and kindness and tolerance and belonging. There were no “in groups” and decisions were parish wide and transparent.

The externals were not important; no one could afford anything anyway. There were daily masses and Sunday masses, baptisms, confessions in four languages and weddings, potluck feasts with arroz con gandules paired with ham and wiener schnitzel, Breakfasts with Santa, midnight mass with standing room only and Easter Vigil, and always someone willing to help out. The annual fundraiser was “Summer in the City” held for several years in Lincoln Park with a permit and then in local establishments with a yard or patio that opened on a Sunday afternoon just for St. Teresa. Everyone could afford to go and did go. It was in this period that the stellar icons that adorn the church were painted and donated.

Emanating the strongest light over and through all of these activities was the Spirit of Matt Hoffman. Some Father Hoffman stories might help to explain this Spirit. Perhaps the most amazing one was that Matt Hoffman left St. Teresa’s and volunteered to be assigned to an even poorer parish on the south side. After his rectory and garage at this new parish had been broken into so many times that there was nothing left to steal including the rims and tires on his car, Cardinal Bernadin personally went down to the rectory with his car and driver and told Matt Hoffman that he had come to move him into the rectory at a neighboring parish where another priest lived. It was the Cardinal’s sincere worry, as expressed to Father Hoffman when he resisted the move, that the next person who broke in would be so angry to find nothing left to steal that Matt would be murdered in his bed. He was moved with reluctance and continued to minister to his parish. Matt Hoffman taught English at Quigley seminary for years and so impressed his student priests that his funeral was packed with them. He was a founding member the Association of Chicago Priests and asked the Archdiocesan powers at one of the meetings of the ACP with all parish priests what the diocese was doing to care for parish priests who with the diminution of their numbers lived lonely lives in solitary rectories. He learned to ski at 50 at the behest of his three regular priest vacation companions and continued to accompany them on skiing vacation even when he needed to take an oxygen tank because of the altitudes. His application to take a poetry writing course one summer at Harvard after he retired and, to his great disappointment, was turned down because of his age. All this Spirit, he brought to his years at St. Teresa and left as his legacy.

Emanating the strongest light over and through all of these activities was the Spirit of Matt Hoffman. Some Father Hoffman stories might help to explain this Spirit. Perhaps the most amazing one was that Matt Hoffman left St. Teresa’s and volunteered to be assigned to an even poorer parish on the south side. After his rectory and garage at this new parish had been broken into so many times that there was nothing left to steal including the rims and tires on his car, Cardinal Bernadin personally went down to the rectory with his car and driver and told Matt Hoffman that he had come to move him into the rectory at a neighboring parish where another priest lived. It was the Cardinal’s sincere worry, as expressed to Father Hoffman when he resisted the move, that the next person who broke in would be so angry to find nothing left to steal that Matt would be murdered in his bed. He was moved with reluctance and continued to minister to his parish. Matt Hoffman taught English at Quigley seminary for years and so impressed his student priests that his funeral was packed with them. He was a founding member the Association of Chicago Priests and asked the Archdiocesan powers at one of the meetings of the ACP with all parish priests what the diocese was doing to care for parish priests who with the diminution of their numbers lived lonely lives in solitary rectories. He learned to ski at 50 at the behest of his three regular priest vacation companions and continued to accompany them on skiing vacation even when he needed to take an oxygen tank because of the altitudes. His application to take a poetry writing course one summer at Harvard after he retired and, to his great disappointment, was turned down because of his age. All this Spirit, he brought to his years at St. Teresa and left as his legacy.

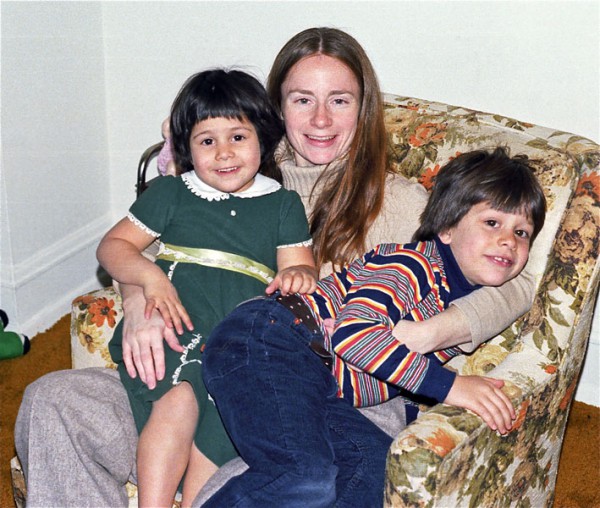

He left many legacies to many, but I can speak best to my own personal ones. So much a part of my extended (parents, spouse, children, siblings) family did Matt Hoffman become that my son Matthias Robert is named after him and my father. Matt Hoffman is his godfather. Also in this period, my daughter Summer sat for days in the rectory pouring over parish records on some kind of history project for school with Father Hoffman supplying milk and cookies. Under Father Hoffman’s spirit, Carmen Ubides and I, from such different backgrounds it may as well be Venus and Mars, became friends and confidants and have remained so for 45 years. After he retired, I visited Matt, went to meals with him and took him shopping regularly after he moved to a retirement home. He introduced himself to every server in every restaurant he ever ate a meal at, asked the server’s name and had a personal conversation during the server’s trips to and from the table. Fr. Hoffman was a simple parish priest but his funeral mass and burial were attended by more fellow priests and institutional hierarchy than is typical outside of the Vatican. Like the brilliantly colored icons hanging in St. Teresa’s Church, he was and is my icon of a good man and a good priest.

He left many legacies to many, but I can speak best to my own personal ones. So much a part of my extended (parents, spouse, children, siblings) family did Matt Hoffman become that my son Matthias Robert is named after him and my father. Matt Hoffman is his godfather. Also in this period, my daughter Summer sat for days in the rectory pouring over parish records on some kind of history project for school with Father Hoffman supplying milk and cookies. Under Father Hoffman’s spirit, Carmen Ubides and I, from such different backgrounds it may as well be Venus and Mars, became friends and confidants and have remained so for 45 years. After he retired, I visited Matt, went to meals with him and took him shopping regularly after he moved to a retirement home. He introduced himself to every server in every restaurant he ever ate a meal at, asked the server’s name and had a personal conversation during the server’s trips to and from the table. Fr. Hoffman was a simple parish priest but his funeral mass and burial were attended by more fellow priests and institutional hierarchy than is typical outside of the Vatican. Like the brilliantly colored icons hanging in St. Teresa’s Church, he was and is my icon of a good man and a good priest.

Image Credits

“Black-Panther-Party-founders-newton-seale-forte-howard-hutton” by Source. Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Black-Panther-Party-founders-newton-seale-forte-howard-hutton.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Black-Panther-Party-founders-newton-seale-forte-howard-hutton.jpg